By Ruth Simbao, SARChI Research Chair in Geopolitics and the Arts of Africa at Rhodes 老虎机游戏_pt老虎机-平台*官网

Sam Nzima, the photographer who captured the iconic image of the 1976 Soweto Uprising passed awayon May 12, 2018. The photograph was one of six frames showing Mbuyisa Makhubu carrying 12-year-old Hector Pieterson who was shot by police, and Hector’s sister, Antionette Pieterson (now Sithole) running alongside.

Sensing the impact these photographs would have in exposing the cruelty of apartheid, Nzima hid the roll of film in his sock. Following the release of the photograph worldwide, the police were ordered by the apartheid government to kill Nzima if they found him taking any photographs. When he was summoned to John Vorster Square, the dreaded police headquarters in Johannesburg, he went into hiding. His career as a journalist for the anti-apartheid newspaper, The World, came to an abrupt end.

While Nzima’s photograph quickly became known as the most evocative photograph to emerge from the struggle against apartheid, initially few people associated the photograph with him. At times it was erroneously attributed to acclaimed photographer Peter Magubane.

Just over a year later The World was banned by the apartheid government, but Nzima’s photograph lived on. Printed onto numerous T-shirts, posters and pamphlets, it became virtually synonymous with protest.

Protest and (over)exposure

What happens to images that appear over and over again in the visual economy? Art historian Colin Richards suggests that powerful images can also be extraordinarily vulnerable, for when they are sensationalised overexposure can weaken the historical moments they capture.

In 1989 liberation struggle stalwart Albie Sachs made a similar assertion when he presented the paper “Preparing Ourselves for Freedom” at an ANC in-house seminar on culture. He argued that, the power of art lies precisely in its capacity to expose contradictions and reveal hidden tensions.

Sachs warned that the repetitive use of visual portrayals of struggle icons such as guns, clenched fists and protest slogans merely flattened meaning and impact. His call to ban the statement “culture is a weapon of struggle” was contentious and ignited an intense debate. Respondents such as historian Rushdy Siers argued that culture is based on lived experience, and “vivas, raised fists… AK’s and Amandlas” were indeed the lived experiences of cultural workers.

The photograph’s shadow

In Nzima’s original photograph the three figures cast a deep shadow on the ground. However, many versions of this image that were silkscreened onto protest posters and T-shirts flattened the image and omitted the shadow. Artworks that drew from this image, such as Kevin Brand’s duct tape mural on the outside wall of Musée de Dakar (1998) in Senegal, and Ernest Pignon-Ernest’s public murals at Warwick Triangle (2002) in Durban reintroduced the shadow, suggesting that this powerful photograph withstood potential numbing often induced by repetition.

Recalling philosopher Roland Barthe’s assertion that texts need shadows in order to be productive and subversive rather than sterile, the shadow of this photograph and its numerous re-representations can be read as a metaphor for the rich debate that this image continues to bring to the surface. Commemoration is contested, and Nzima’s photograph has raised numerous debates.

An important question to ask is: to what degree does a powerful photograph reduce commemoration to the name of one person, thus overlooking the tragedies of other individuals who were killed on the same day? Due to the wide reach of Nzima’s photograph, it was initially believed that Hector Pieterson was the first student to be killed by the police. But oral testimonies suggest that Hastings Ndlovu was not only the first to be gunned down, but was also deliberately sought out by the police.

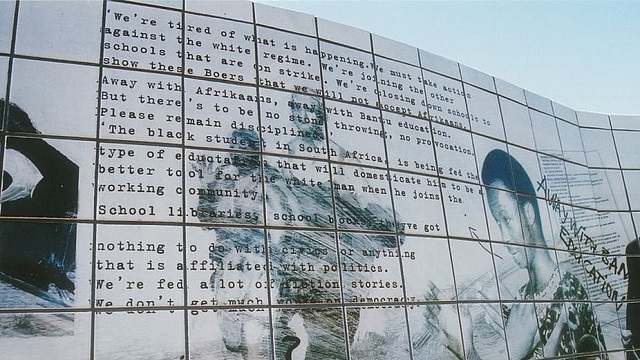

Artist Johannes Phokela created a ceramic memorial wall that is dedicated to student leader Tsietsi Mashinini. It was unveiled at the 30th anniversary of June 16 in 2006. The memorial is shaped like an exercise book and the grouting between the tiles represents the lines on the pages.

This commemoration does not erase the memory of Hector Pieterson. Nzima’s photograph is portrayed behind the words of Mashinini that are written on the wall. Representing an open book, the commemorative wall suggests a willingness to accommodate counter-narratives of the uprising. As such, the horrific events of this day are not flattened, but are presented as stories or texts with shadows.

History reanimated

The persistence of Nzima’s photograph is remarkable. Not only was it used on T-shirts, posters and pamphlets in the 1980s, but it has reappeared in the form of artworks, memorials, monuments, and numerous cartoons, including the work of cartoonists Sifiso Yalo and Zapiro. The fact that it raises ongoing debate is important, as this works against the grain of much government-led commemoration that tends to reduce historical events to one-dimensional interpretation.

One of the most poignant forms of response to this iconic image is the live re-enactment of the photograph. When I participated in the 2006 commemorative march from Morris Isaacson High School to the Hector Pieterson Memorial in Orlando West, a group of young people ended the march with a re-enactment of the famous Nzima photograph.

This performative engagement with Nzima’s photograph, like the recent correlations between the Soweto Uprising and the Rhodes Must Fall movement, is critical in terms of the reanimation of history. Not only are the historical events of Nzima’s photograph recalled, but new generations redefine events on their own terms and in relation to their own contexts. This brings alive the shadow of this iconic photograph.

Source: https://theconversation.com/capturing-the-soweto-uprising-south-africas-most-iconic-photograph-lives-on-98318