“It is often said by the members and supporters of the executive that policymaking is its domain and has nothing to do with the courts. Indeed, it is said that court decisions that impact on policy made by the executive violate the separation of powers. This effort at defending the cabinet overlooks the fact that as soon as executive policy translates into law or conduct, that law or conduct must be consistent with the constitution. Otherwise, courts have no choice but to do their duty and declare that law or conduct invalid.”

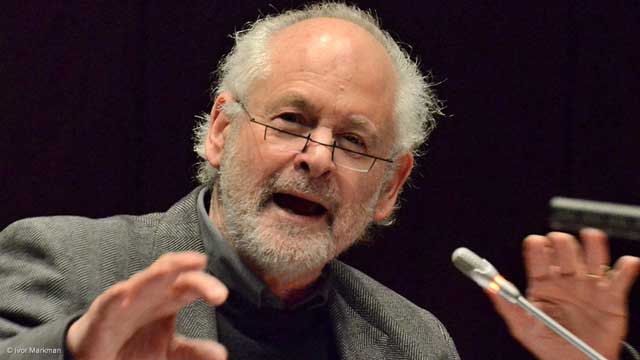

-retired Constitutional Court 老虎机游戏_pt老虎机-平台*官网 Zak Yacoob, Sunday Independent 21 May 2017

Last week there was a march against “judicial overreach” in KwaZulu-Natal. This refers to the claim that courts are interfering in areas that according to the doctrine of the separation of powers are the prerogative of the executive or legislature. Attacks on the judiciary have been a periodic feature of rule under Jacob Zuma, sometimes muted, sometimes more strident. A commitment to mutual respect emerged from a meeting between the judiciary and government leaders in late 2015, but it is now under strain.

In the history of South Africa the judiciary has had a mixed record in the eyes of those who opposed apartheid. Some of the sentiments of that period may linger on in the consciousness of many people. On the one hand, the lower courts were widely perceived as implementing the harshest laws of apartheid without mercy and often mirroring the racist sentiments of the apartheid rulers. This was sometimes seen in utterances of Magistrates or Bantu Affairs Commissioners and disparity in who was convicted of offences and the sentences meted out to black and white. This was especially true with regard to black convictions for murder and rape of whites compared with very limited white convictions.

At the level of the Supreme Court, there was a sense of professionalism in the self-image of the bar and bench, modelled on that of the United Kingdom, from where the legal profession derived. Even in the case of party partisan appointments, many of these convinced themselves that they were in fact appointed on merit and acted that out. Once on the bench some judges made decisions against the National Party government and manifested a significant degree of independence.

This independence should, however, not be exaggerated insofar as judges pledged in their oath of office to apply the laws of the Republic of South Africa of the time. In other words, whatever their personal inclinations or any repugnance they may have felt towards the laws of the day, those were the laws they were obliged to apply in court cases.

Nevertheless there was room in the application of laws, no matter how harsh the intention may have been, for more than one interpretation on certain matters and some judges took decisions that construed the impact of repressive laws in a manner that was as limited in its invasion of personal freedom as possible. When faced with ambiguity they saw their professional obligation, as members of the legal profession to align themselves with a particular set of traditions and ethics that limited state repression. This led to some people being freed from detention or restraining orders being issues against the police.

It compelled the government to continually amend or introduce new laws to limit the scope of judicial intervention by inscribing in the legislation that subjective intent in making a decision would suffice for many repressive actions by the authorities to be valid. Thus where someone was restricted in one or other way, this left very little room for examining whether or not it was justified, even if it harshly invaded the freedom of individuals or groups of individuals. That the Minister or applicable official had applied his or her mind was sufficient and could not be set aside by any court.

It became necessary and very difficult to show that some or other subjective factors had come into play rendering the decision such that it was clear that the official had not applied his or her mind. This was much narrower in scope than that of the “irrationality” recently under scrutiny over President Zuma’s dismissal of the Finance Minister and others. The basis of the claim of irrationality today is an attribution of subjective irrationality by relating the decision to objective facts that were know to exist. The judicial scrutiny and decisions related to earlier findings of dishonesty against Menzi Simelane, before he was appointed head of the National Prosecuting Authority and similar findings before the appointment of Mthandazo Berning Ntlemeza as head of the Hawks. This stood as evidence independently of whatever may have been in the mind of the official who made the decision that was challenged.

Under apartheid, many courts heard political cases where those accused had been tortured and provided testimony of such torture. Individuals who had been tortured generally had no witnesses while the police could back up one another’s evidence. My impression is that if the question of torture related to a confession, the judges would read the confession. If they felt the person was guilty as charged, they would work backwards and find a way of dismissing the allegations of torture and often commended police for their work.

These experiences may still colour the way the courts are seen today. In the course of the liberation struggle, the ANC and SACP were in the forefront of an insurrectionary approach to struggle. That way of thinking led to certain expectations of a future government: establishing a state of people’s power and in this understanding, those of us who were involved did not place great value on notions of independent institutions of state and the judiciary. That is not to say that we opposed them but they were not our main preoccupation at the time.

These ideas were less widely diffused than notions of popular power being wielded in order to remedy the injustices of apartheid and transform the character of the state, from one serving only whites to one that was responsive primarily but not exclusively to the most oppressed and exploited. This would be, amongst other things, through state control, seen as then embodying the will of the people, over key industries and institutions.

Even when the ANC constitutional committee started to advance notions of constitutional democracy with a bill of rights and constitutional supremacy in the 1980s, most ANC cadres were still preoccupied with insurrectionary activities and may not have absorbed all the implications of these shifts. Although I was trained in law I was one of those who were sceptical of what could be expected of the legal system and the constitution, even in a democratic South Africa.

Contextually, it should be borne in mind that a range of proposals aimed at protecting minority privileges and through constitutional stratagems trying to limit the power of the majority had fuelled this cynicism. One thinks of the “Buthelezi Commission” and various schemes for “consociationalism”, basing government on ethnic representation.

Also, we had seen how the judiciary had played a role in hampering progressive transformation in societies like Chile under socialist president Salvador Allende, before the infamous Pinochet coup d’état, in 1973.

We had never experienced a rights-bearing legal system and notions of constitutionalism were widely associated with attempts to limit the character and scope of post-apartheid freedom.

In the 1996 democratic constitution the shift in status of the judiciary and constitution went far beyond that which was found in the UK, which had previously been one of the main alternative sources for influencing legal approaches under apartheid. While South Africa had laws that were racially discriminatory unlike the UK, both countries shared a belief in parliamentary supremacy. As AV Dicey succinctly put it, parliament could “make or unmake any law”, and that was true in the UK and in South Africa, although unlike Britain South Africa did have a written constitution. But what parliamentary supremacy meant is that whatever parliament decided was supreme. There was no higher law. The constitution in apartheid South Africa was not a higher law. It was a piece of legislation like any other law, though there were distinct procedures required to change some provisions.

Whatever existed in previous laws in the UK could be overridden by subsequent parliaments and whatever was in the South African constitution could be overridden by parliament –as long as it observed the legal requirements for making a law.

When the famous Coloured voters cases, deriving from the attempt by the apartheid government to remove Coloured voters from the common voters roll, were decided by the then Appellate Division of the Supreme Court, they at first prevented the apartheid regime from removing Coloured voters. This was because parliament failed to observe provisions requiring a two-thirds majority in a joint sitting of parliament –laid down in the constitution –before franchise and language rights could be altered.

What is very different about the current constitution, is not only that there are no longer provisions entrenching apartheid discrimination, but also that the constitution is supreme. Any law of parliament or any action of a minister may be subject to legal scrutiny insofar as these may have violated provisions of the constitution.

But it also applies to the substance of the law, insofar as the Bill of Rights lays down obligations on the part of the state to meet basic needs. This has led to judicial decisions compelling the authorities to provide these, including housing and elements of health care or to desist from evicting people without alternative accommodation.

Under the present constitution not only is apartheid supposed to be no more but also neither parliament nor the executive is supreme. The constitution stands above these and it is the courts whose authority is invoked to decide where there are breaches of constitutional obligations.

This does not mean that courts can hear a case where there is simply a breach of trust or an obligation between a political party and its constituents, as when it fails to meet a campaign promise or undertaking, when a party is indifferent to its supporters to whom it promised this or that. These may or may not also entail legal obligations, depending on the character of the undertaking.

Where the executive or the legislature fails to meet a constitutional obligation, as in the case of the Nkandla spending which entailed diversion of funds towards private benefit and failure to hold the president to account, then the courts can adjudicate. Likewise, in the case of social grants. There was an obligation that was not discharged and the courts were called on to ensure that legal obligations were fulfilled. It should be emphasised that in all of these cases, the courts do not seek out litigants to appear before them. The courts only enter or engage with these questions when litigants approach them.

When opposition parties and civil society went to court over Nkandla and social grants there were clear legal obligations that had been violated. In the case of the cabinet reshuffle and the secret ballot one can hear in some judicial statements that the courts are much less keen to be involved. They fear that if they pronounce on these matters they may usurp decisions that ought to be made in parliament or by the executive itself. I am not saying that there will not be such decisions (and there has been on the cabinet reshuffle), but it is a terrain where the judiciary will be slow to act.

Even if the opposition succeeds in enlisting judicial support for various constitutional matters, it needs to be careful that “lawfare” does not become a substitute for winning political support in conventional ways, building its support base and constituency. The resort to the courts over Nkandla and the social grants issue became vital because parliament, through the ANC’s majority, was not holding the executive to account. In a sense the judicial decision was both a legal victory and a political gain, defending hard won rights of the people of South Africa.

Despite these victories, opposition parties and civil society formations that may hope to play a role in revitalising South African democratic life need to be cautious in resorting to courts. A judicial victory is not the same as what is gained through political organisation and through winning political support as an organisation or for a political cause or vision. It is very important that the courts are not seen as substitutes for doing the work that is necessary to build an alternative vision and also organisational work needed to mobilise and activate South Africans from all walks of life.

Raymond Suttner is a scholar and political analyst. Currently he is a Part-time Professor attached to Rhodes 老虎机游戏_pt老虎机-平台*官网 and an Emeritus Professor at UNISA. He served lengthy periods in prison and house arrest for underground and public anti-apartheid activities. His prison memoir Inside Apartheid’s prison will be reissued with a new introduction covering his more recent “life outside the ANC” and will be published by Jacana Media late in May. He blogs at raymondsuttner.com and his twitter handle is @raymondsuttner